Fish Farm Forum is pleased to host this editorial page on behalf of Pharmaq.

Pharmaq

Race to control bacterial disease which threatens Irish salmon production

The bacterium Piscirickettsia salmonis, which causes the disease salmonid rickettsial septicemia (SRS) in Atlantic salmon, is becoming an increasing concern on fish farms in Ireland.

SRS has previously caused major issues in the Chilean salmon industry, yet outbreaks in the North Atlantic have tended to be relatively mild. Things are changing, however, with cases in Ireland increasing in incidence and severity, said Felix Scholz, PhD, head of clinical services at PHARMAQ Analytiq Ireland.

Fighting SRS drives costs upward

Treatments for the disease were very rarely needed before recent years, Scholz told an audience at an industry event in Inverness. Now, though, mortalities are rising and so too the cost of treatments. Indeed, SRS is the biggest driver of antibiotic use in Irish salmon aquaculture since 2019.

The pathogen is genetically diverse, with three accepted genogroups, but the distribution and significance of different strains is yet to be fully understood. PHARMAQ Analytiq work has found the genotype EM 90 to be associated with recent outbreaks in Ireland.

“[Understanding genogroups] is not just an academic concern, because they vary very substantially in their pathogenicity, culture characteristics, virulence and a number of very practically relevant points,” he said.

Genotypes present and associated with disease in Ireland and the UK remain poorly understood, he noted, and data from the countries has largely not been included in published phylogenetic studies.

Many factors at play

The presence of P. salmonis does not necessarily lead to disease, and other factors influence outcomes such as warmer water, environmental conditions and other infections. This makes it hard to predict the course of the disease.

“In my experience, it’s very rare to see a clean cut rickettsia outbreak with nothing else going on. The triggers could be environmental issues, such as harmful algae blooms or jellyfish,” he noted.

“Mortality is typically multifactorial, and it can be very hard to accurately judge how much of it is due to rickettsia and how much of it is due to other factors which might be present on site.”

Diagnostic complications

In the light of the recent uptick in mortalities, monthly sampling is now taking place on Ireland’s high-risk salmon aquaculture sites.

There are a number of clinical signs associated with disease, he continued, such as skin lesions, bloating, pale gills and loss of equilibrium. However, mortalities can also occur with no signs, further complicating the picture.

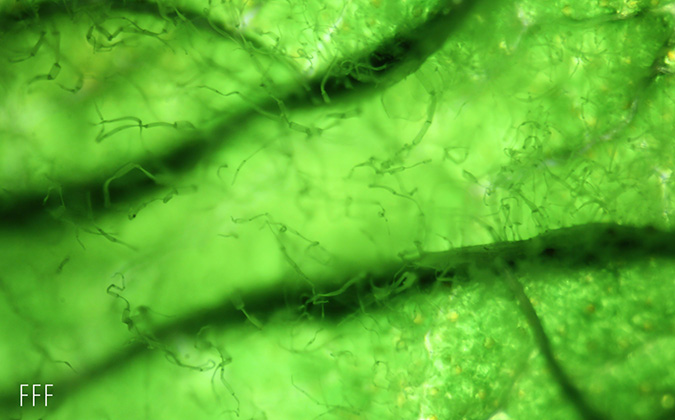

Histopathology should always be part of initial investigations where the disease is suspected, he continued, while diagnostic technologies such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing are available to provide in-depth analysis.

“It is immensely important, in my opinion, to take histology to assess the extent of a systemic pathology but also to properly characterize what else is going on in the fish,” he said.

“You need to know what state the gills are in, or if there are any other underlying viral pathologies, for example.”

Identifying the presence or absence of strains of interest is useful, he said, but understanding where it has originated from is tougher.

It is necessary to consider the “epidemiologic triad” of pathogen, fish and environment when tackling the threat of SRS, he explained. Disease can originate from other farms in a locality and the marine environment, with gills the suspected main point of entry. SRS has also been diagnosed in lumpfish in Ireland but not in modern recirculating aquaculture facilities, and they are unlikely to introduce the infection.

Accessing control options

Managing other conditions which predispose salmon to SRS, as well as effective cleaning and disinfecting, are important parts of control efforts, Scholz said. So too is a proper diagnosis and effective characterizing of mortalities.

Selective breeding and vaccination can also play a role; however, while there are commercial vaccines licensed for use in Chile, there is no similar regulatory approval in Europe. SRS being accepted in the class of “emerging disease” may change this, but such a move is not expected soon.

“I doubt that a vaccine is going to be the silver bullet that solves the problem for us. But I do see this as a necessary component to get in our toolkit to get on top of the challenge we’re having right now,” he stressed.

As things stand, producers in Ireland are left with changes in management approaches, biosecurity and antibiotics as their main tools.

Of the latter, florfenicol and oxytetracycline have proved effective at standard dose rates, but antibiotic-residue limits mean that in practice, florfenicol is often the only realistic option, he said. Another current concern is the potential need for repeated treatments, affecting the organic status which many Irish producers have. There have also been issues with supply post-Brexit.

Better understanding of P. salmonis strain diversity, and the effect of strain on disease development, may prove the most fruitful knowledge gaps to fill.

“I think we need better monitoring and accurate characterization of mortality as the basis for treatment decisions. It is possible to ‘jump the gun’ and treat for the rickettsia where it might not be necessary, but it’s a very hard call to make,” he added.

Posted on: March 15, 2023