Taking farmed fish welfare beyond the ‘five freedoms’

Over the last decade, a considerable body of research has demonstrated the capacity of fish to suffer – yet there remain unknowns around what causes the most serious negative impacts on their quality of life.

Low welfare can have knock-on effects in the form of vulnerability to pathogens and lower marketability of stocks. And a greater understanding of this has contributed to a great shift in emphasis. Fish welfare has gone from being a relatively novel concept to embedded in the mindsets of producers and certification schemes.

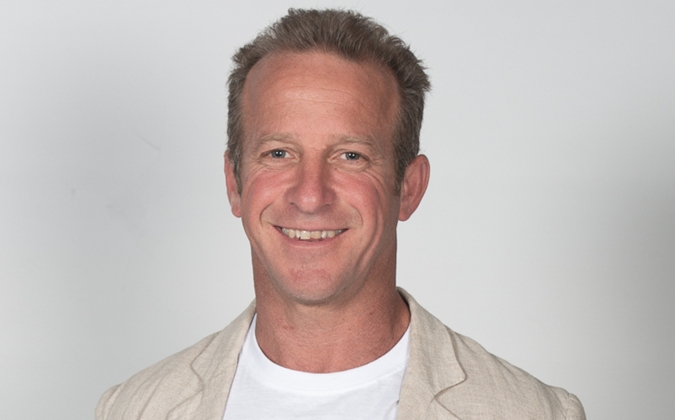

“I think concern for fish welfare is pretty prevalent now,” explained said Dr Huw Golledge, BSc, PhD, chief executive of The Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW) and the Humane Slaughter Association (HSA).

“Even amongst the general public, it’s becoming clear that the old idea that fish don’t feel pain and goldfish have a four second memory is pretty much a myth now. And I think that the aquaculture industry is way ahead of that.”

Traditionally, discussions around animal welfare have been underpinned by the concept of the “five freedoms”. These freedoms provide broad definitions of appropriate measures of welfare, to encourage conscious approaches to working with or caring for animals.

On fish production sites, the challenge is to manage trade-offs between different freedoms effectively. For example, measures such as mechanical delousing safeguard freedom from pain, injury and disease but can cause fear, distress and discomfort.

What are the “Five Freedoms?”

In response to concerns about animal welfare in livestock husbandry, The Five Freedoms were established by the UK Farm Welfare Council in 1979, and have since been accepted by major organizations and professionals worldwide. They are:

- Freedom from hunger and thirst

- Freedom from discomfort

- Freedom from pain, injury or disease

- Freedom to express normal behavior

- Freedom from fear and distress

Bringing ‘quality of life’ thinking to aquaculture

The “five freedoms” approach is a good place to start exploring welfare issues, but some suggest that an updated, further-reaching vision of welfare is required. Golledge is inclined to agree.

“There’s been a traditional sense in welfare that abolishing the negative is what we want to do. We want to avoid disease and injury, or keeping animals way outside the physical parameters that they thrive in, such as too cold, too hot, or too crowded. They are the basics that you’re going to be thinking about in aquaculture,” he said.

“But I think alongside that, we need think about whether animals have any positive experience. What we should be aiming for is having some positive experience in animals’ lives as well as just no negative experiences. Environmental enrichment is possibly what we’re talking about – and that is going to be a challenge in some areas of the industry.”

What is the impact of captivity on farmed fish?

The effect of restrictions on the natural behavior of fish is one area that needs further research, suggested Golledge.

“We know that some of the animals that are most at risk of having poor welfare in captivity are those that range over very large distances, like polar bears. Being a salmon might be somewhat equivalent to that, given we’ve got a marine carnivore that travels large distances, that’s being prevented from doing that. I think that would be a really interesting question, to try and understand if that really is the same.”

There are new techniques that can look at changes in animals’ brains over their lifetimes and identify markers associated with stress, explained Golledge.

“You can imagine doing that with fish, and asking, if you are a migratory species being prevented from migrating is that very different to being a species that that travels very short distances? Is that species more likely to be have a higher welfare in captivity? And that’s not necessarily as obvious as it might seem.”

Improving slaughter methods across fisheries

Humane slaughter is a fundamental component of fish welfare. Golledge pointed to the impact of previous HSA funding of some of the early research, alongside commercial manufacturers, into electrical stunning of fish. This resulted in systems now in common use.

The HSA is currently funding £1.7million (US $2.36 million) of research on the humane slaughter of fish, crustaceans and cephalopods, looking at a range of species that do not have established stunning parameters. The HSA has also funded work to examine the feasibility of routine stunning for wild-caught fish. Results from these studies will be presented at the organization’s 2022 conference.

“People often operate under the assumption that wild-capture fishing is more humane, but we’ve also been supporting work on incorporating stunning in this setting, because post capture, it can be quite challenging in terms of welfare,” he explained.

Knowledgeable public, engaged industry

Consumers have proven willing to pay more for higher welfare standards and this is a strong driver of improvements, Golledge noted, but research can help inform the public about the nuances of welfare challenges in the fisheries industry.

“It’s important to have knowledgeable consumers who understand the welfare implications of both wild-capture and farmed fish, and even where their fish comes from in the first place. This is a challenge, and not unique to fish, as the level of understanding about any production system is not high amongst the public.”

Working with aquaculture producers is vital to the spread of ideas on improving welfare, he said, as what works under research conditions will not always work in day-to-day practices on fish farms.

“A thing we’ve always done when we’re funding major pieces of research is doing feasibility analysis. Dialogue is important, because having some welfare organization come along and tell you what you should do, when you know that it’s completely impractical or it’s never going to be economically feasible, is pretty pointless,” he added.

Posted on: May 04, 2022